The Chanteloup Pagoda

In 1761, the Duc of Choiseul, then Prime Minister of Louis XV, bought the Chanteloup estate, shortly after being appointed Governor of Touraine. From 1765, he had the castle extended and modernised, and the gardens enlarged. After falling into disgrace, he was exiled from Paris in December 1770 and settled at Chanteloup, where he completed the renovations. There he held a brilliant assembly, which was considered a rival to Versailles.

The “Duke of Choiseul’s Folly” or “Monument dedicated to Friendship” was built by the duke in 1775, after his exil from the court of King Louis XV, as a tribute to all his friends who had shown him their loyalty.

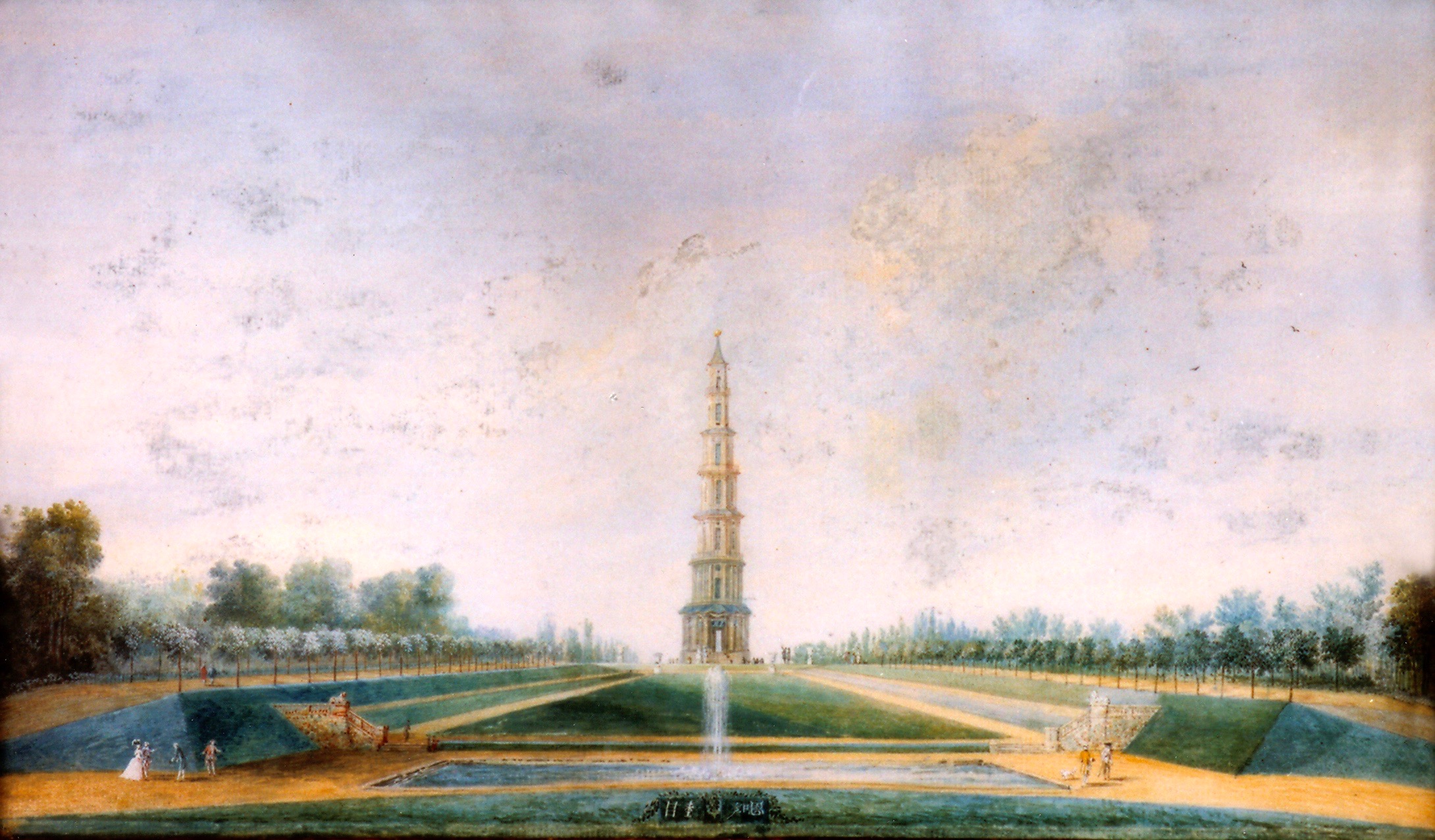

The slender Pagoda of Chanteloup, designed by architect Louis-Denis Le Camus, was inspired by the Chinese pagoda at Kew Gardens, designed by the great William Chambers. Le Camus also designed a small Anglo-Chinese garden, located beneath the pagoda in the north-east square, with a kiosk, river, small pond and ice-house. The Scottish gardener Mac Master, a member of Thomas Blaikie’s entourage, also worked on the estate.

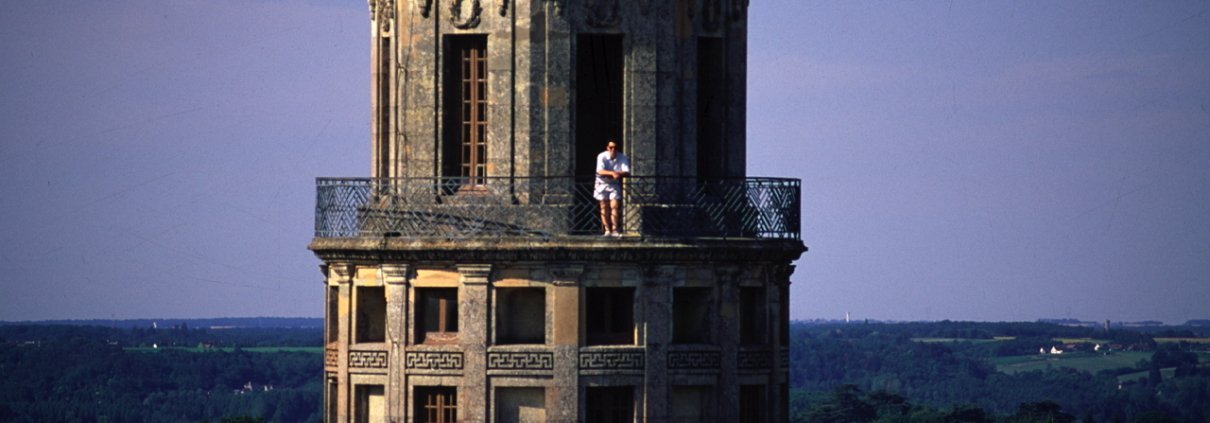

Famous for its beauty and the surprise it creates on the site, this 44-metre-high monument is supported by a peristyle of 16 columns and 16 pillars. Each of the 7 floors is built as a dome.

Each dome is bisected by a narrow, sloping staircase that rises to the top.

The staircase is made of mahogany, with the exception of the 1st floor, which is made of stone and guarded by a wrought-iron banister adorned with gilded double C-shaped intertwined bronzes bearing the initials of Choiseul and his wife Crozat.

It offers breathtaking views of the Amboise forest and the Loire Valley from its summit, and was once used as a hunting lookout.

The Castle of Chanteloup

The Château was built in 1713 by Jean d’Aubigny for the Princess des Ursins.

The estate was bought by the Duc de Choiseul in 1761.

The Duke commissioned the famous architect Le Camus to embellish and enlarge the building.

His exile ended with the accession of Louis XVI, Choiseul died in 1785 and his estate was sold to the Duc de Penthièvre.

In 1802, the château was acquired by Chaptal, a remarkable minister under Napoleon I and a great scientist and creator of chemical processes.

It was at Chanteloup that he perfected the cultivation of beetroot and the extraction and refining of sugar, providing our country with a major new resource. In 1823, Chaptal was forced to sell Chanteloup.

While the Duc d’Orléans, the future King Louis-Philippe, was buying the Pagode to join the forest he had just acquired, the castle fell into the hands of those property dealers infamously known as “La Bande Noire”. The furniture was sold, the castle demolished and the gardens subdivided.

Today, all that remains of the sumptuous princely residence is :

• The Pagoda

• The large half-moon-shaped lake, extended by a large canal, with its crow’s-foot perspective,

• The Petit Pavillon du Concierge, which houses a permanent iconographic exhibition retracing the history of the château and its gardens,

• The two charming pavilions in the purest Louis XVI style on the Amboise side, which at the time marked the entrance to the estate through the “Grille Dorée”.

The Chanteloup Gardens

The gardens at Chanteloup, which were very extensive – covering no less than 4,000 hectares – were created throughout the 18th century.

They were begun in 1710 by Jean d’Aubigny. At that time, the garden developed a very classical formal layout: a kitchen garden, a “formal” garden around the castle and a wooded garden with copses and hedges laid out in a regular pattern.

In 1761, the Duc de Choiseul commissioned his architect Louis-Denis Le Camus to make some splendid improvements.

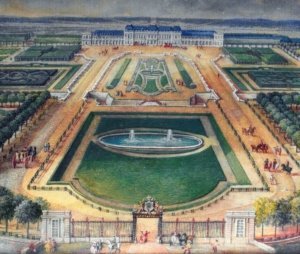

As at Versailles, there was :

• The “Petit Parc”, with its regular layout, surrounding the château with flower gardens and magnificent water features.

• The “Grand Parc” extending into the forest, with crossroads, stars and long, straight avenues.

Choiseul wasted no time in enhancing the gardens to match the palace. He devised a grandiose plan, divided into two stages:

• He began with the “Grand Parc”, opening seven wide garden avenues converging at a central point – where the Pagoda would later be built.

• He then laid out the gardens of the “Petit Parc”, stretching over more than a hundred hectares, according to a design by Jean d’Aubigny, based on a plan that has survived to this day.

To supply the numerous “water games”, Choiseul undertook considerable work to bring up the water in abundance.

Later, at the highest point of the Chanteloup site, he had a half-moon-shaped lake dug. To supply it, he did not hesitate to connect it to the Etangs de Jumeaux located in the forest more than 12 km away as the crow flies, with a difference in level of only 6 metres, by a canal crossing a valley via a lead siphon! Around 1770, Choiseul undertook to extend this stretch of water with a Grand Canal, six hundred metres long and one hundred metres wide.

To the north of the wooded garden, he had a charming little rectangular garden laid out, known as the “Orange Garden”. Choiseul later transformed the woodland garden into a picturesque garden in the style known as “Anglo-Chinese”, with a meandering river whose waters flowed from a height of four metres through a graceful nymphaeum feeding the central water circle of the Orange Garden.

Giving in to the taste of the time for China, rejecting the rigorous aristocratic symmetry of the French garden, Choiseul commissioned Le Camus to redesign the gardens at Chanteloup. Drawing his inspiration from Anglo-Chinese gardens, Le Camus turned the woodland garden on its head: the rectilinear ponds were demolished and replaced by a meandering river winding its way through rockeries, bridges and waterfalls until it ran out of water in a nymphaeum. The straight lines of the avenues are replaced by winding paths through factories, an ice house and a kiosk.

However, Choiseul hesitated between the “naturalness” of the Anglo-Chinese garden and the rigour of the French garden. This is why he ended the garden’s fantasy by having a chinoiserie (the Pagoda) built in the purest Louis XVI style at the centre of a perspective of the greatest classicism.

The gardens were devastated during the French Revolution.

What remains today is

• The half-moon-shaped Pièce d’Eau (water feature), extended by the Grand Canal lined with plane trees, which became a marsh and was transformed into a boulingrin (lawn bowling green).

• The forest paths of this 14-hectare park and the grand perspective of the seven crow’s-foot paths.